How a musician's collective carves a pathway for platforms to be owned by their communities

👋 Hey, it’s Jaime. Welcome to my weekly newsletter where I share how thriving open source projects grow their communities.

Subscribe to get access to these and all future posts.

Today I’m going to show you how Subvert is trying to create a platform cooperative owned by the musicians and labels.

This is like creating a platform in hard mode: there are zero books and very few resources on how to start cooperatives, you can’t get investors money to build it, and you still need to gather a community and create network effects to convince professionals and users to adopt your service against established solutions.

This shouldn’t be read as one-size-fits-all advice since there is a bigger field of platform coops that each need to be tailored to unique needs and geographic contexts. And even if it’s still early, hopefully this article can bring an extra piece for those who’d like to build alternatives to the big platforms that got powerful enough to usurp our relationships and use them against us.

We’ll cover:

Understanding why previous platform coops failed

Using shared ownership as a competitive advantage

How to craft a compelling vision for a collectively owned platform

Solving the Freerider Problem

How to get people to believe you can pull it off

Funding a platform coop when you don’t have the platform nor the community

Getting the collective going

What if you still fail?

TL;DR: How can you replicate some of Subvert’s successes?

Read time: 16-ish minutes

It’s one of the greatest times to create an alternative to the monopolistic platforms we used to love but feel trapped by today.

Enshittification, the process through which online platforms decline in quality, became the 2023 Word of the Year.

Google was declared guilty of maintaining an illegal monopoly in internet search and advertising markets, and must sell Chrome.

Adobe couldn’t buy Figma because UK and European regulators concluded it was going to eliminate competition.

Bluesky’s competition is forcing Thread’s to respect what its users want instead of forcing their algorithm on them

So, even if for a long time the big platforms we relied on have turned against their communities, we have tools at our disposal to help us create community-friendly alternatives that, instead of squeezing their users, serve them.

Especially if you know that other people want the same thing.

Imagine what the world would be like if we had the equivalent of Uber, Airbnb, Facebook or Twitter, but owned by their users.

As Austin Robey, Subvert’s co-founder, says, we could wait for the next platforms to betray our trust and then protest. But protest alone won't build the infrastructure we need.

Instead of enjoying the “free” or convenient products they provide, the alternative involves asking new platforms to include:

Proposing accountability agreements with the founders

Building mechanisms for community oversight

Agreements for greater transparency

Securing board seats to ensure users have a voice in major decisions like acquisitions

And most of us want to opt out of Big Tech, but not alone.

Once we realise that Big Tech can’t survive without its users, we owe it to the world (and ourselves) to set up our own alternatives.

Even if we might need laws that prevent intermediaries from gaining this much power in the first place (that’s covered here), today I’m going to show you how Austin Robey is creating Subvert, a music marketplace owned by the musicians who use it, and how it can inspire us to create a new type of platform owned by their users, in 10 easy steps.

Let’s dive in.

The trigger: Bandcamp sells out to different holdings

In March 2022, Bandcamp announced that its founders had sold the company to Epic Games, the makers of Fortnite, creating lots of uncertainty and a feeling of betrayal for the hundreds of thousands of musicians who relied on the platform.

A year and a half later, Bandcamp was sold again to the music licensing company Songtradr. Soon after, Songtradr laid off half of Bandcamp’s staff, including most of the union’s bargaining team. This further weakening of the platform created even more uncertainty and anxiety within the user community.

To many, Bandcamp had been the last refuge of independence in a recorded music landscape that had long ago left underground and emerging musicians behind.

And as had happened with other platforms like Uber, Facebook, Figma and others, this event felt like yet another example of a platform positioning itself as an artist-friendly alternative, only to abandon its core values and community. And it was especially disappointing given Bandcamp’s positioning as the last true independent alternative in a streaming-dominated landscape.

So that’s when Austin Robey and Subvert’s team decided to imagine a music marketplace where the community owns the code, controls the decisions, and shares in its success.

Step 0: Preparation — Avoid previous Platform Coops mistakes

In theory, a platform owned by its users is a much more appealing idea than a product owned by a bunch of billionaires in the Silicon Valley.

Platform cooperatives can offer:

more upside for workers and a better community.

more accountability and transparency.

better governance.

And more resilience

Facebook, Twitter, Airbnb or Google are valuable because we all create their content for free, but the platforms don’t give much back and keep making the product and their environments worse.

So entrepreneurs have tried building platform coop alternatives or tried to collectively buy-back these platforms. But these alternatives have failed so far.

As Trebor Scholz points out, “failure rates are not unique to platform coops—over 75% of VC-funded startups fail as well. These challenges are part of innovation, not an indictment of a particular business model.”

But since platform coops have their own systemic reasons for failing, Austin Robey, Subvert’s co-founder, has made a point of learning from past failures and his own attempt as a cofounder of Ampled, a cooperatively-owned crowdfunding platform for musicians, by sharing why platform coops have failed so far and what we can learn from it.

Here are some of his key learnings:

Coops are more difficult to fund than corporations because they don’t have access to capital markets. Investors want to invest in actors with the goal of maximising profits.

Having less access to funding means it’s harder to compete with better-funded actors who only seek to maximise profits over improving the product and services for their users.

Thus, it becomes hard to reach a minimum viable threshold to deliver utility to its members.

A platform coop also has more complex governance than simple top-down management. It’s challenging to ensure members’ pluralist values are represented and put into practice while staying operationally efficient.

And there has also been a lack of quality execution:

Promoting the means over the results: selling a cooperative model is still a very abstract ownership model.

Lack of clear financial benefits to engage people.

Lack of legitimacy and credentials, which led to widespread scepticism.

Ill-suited Patreon-style model for music entailing high switching costs for artist-members in particular. Merely changing labels isn’t sufficient. A cooperative must offer a unique and engaging experience to truly resonate with its audience.

Mistaken assumptions regarding cooperative growth, “We assumed that being a co-op would make it grow. But it wasn’t true.” Simply being a cooperative and offering a distinct ownership model is not sufficient to draw artists or community supporters.

Lack of attractive products. After evaluating the product development and market perception within the cooperative sector Austin states: “The products in the platform co-op space aren’t good. … […] really, really strong products are going to be hard to overtake with this kind of model.”

Lack of awareness of the risk of developing an under-resourced initiative, “if we’re building projects that only last a few years or break and are not properly resourced, then I worry that that is actually worse for users.”

So once Austin Robey lays out the problems platform coops face, this guides the new hypotheses he can work with to develop a new platform coop for musicians:

Develop an operational and relevant way to govern a platform for users with a plurality of views.

Find ways to gather enough funding and resources through an engaged community to have a standing chance and avoid depending on investors who seek to maximise their profits.

Develop a product with a strong and coherent value proposition that’s user-friendly and delivers compelling benefits beyond being a cooperative.

Showcase the credibility and legitimacy of the product and team to build trust.

Stop 1: Embrace sharing ownership like any other innovation

Most founders are motivated to make an impact and have no problem in innovating to create things, or "disrupt.” But most still resist innovations that challenge the the way their organisations are governed and how the resources and power are distributed.

And this is the opportunity Subvert’s teams see to disrupt the current platforms. As Jeff Bezos didn’t say, “Your lack of shared ownership is my opportunity.”

The first platform to succeed at sharing ownership will take over the “enshittified” platforms.

You probably already got the joke, but imagine a world where you can get the same features, content and friends you got on Twitter, Facebook or Google. But instead of them controlling your data and using it against you to squeeze each drop of profit they can get, there is a relevant alternative where the community owns the code, controls the decisions, and shares its success.

Step 2: Crafting a compelling vision for a collectively owned platform

Austin Robey and Ampled’s cofounders already experienced the cooperative startup life with Ampled. And they failed to bring forward a compelling vision that convinced enough potential co-owners to join their platform.

So to try again with Subvert, they created an initial manifesto to lay out how they planned to bring this new recipe to life and also invite the first people to show their interest.

First came the promise:

“Subvert is a Bandcamp successor that is collectively owned, stewarded, and controlled by its community, with 100% of its founding ownership reserved for its artists, community, and workers. We’re building a platform that has artists’ interests, collective ownership, and democratic governance hardwired in its very DNA.”

Second came the response to the recurring objections, like “it’s a utopia,” “why you?, or “it’s too hard”:

“This is not a utopian fantasy. This is a concrete intervention. Building an artist-owned platform is a complex challenge, but it’s one we are uniquely positioned to solve. Our growing coalition includes founders of Ampled, a project that helped pioneer the concept of cooperative platforms, as well as artists, music industry professionals, and specialists in cooperative law and platform economics. Drawing on rigorous research, consultation with diverse experts, and our hard-earned lessons from running platform cooperatives, we've developed a comprehensive, viable plan for Subvert — one that we believe makes collective ownership not just a possibility, but a winning strategy.”

Third, lay out the goal for the platform, its community, but also the extended industry:

“Subvert’s primary goal is to create a collectively owned alternative to Bandcamp—a marketplace that makes it easy for artists to directly sell physical and digital work, while also giving them greater control over their own destiny. But our vision extends further. We're not just building a platform; we're creating a new model for an artist-owned internet. Our goal is to create a replicable framework that can be applied across various services and industries, challenging incumbent platforms through the power of collective ownership.”

In parallel, they created a series of tweets that go further and illustrate the milestones they have in mind to reach their goals:

This article is already long, so I won’t dive into this much more, but if you’re interested, it’s definitely worth diving deeper into their manifest, tweets and blog posts.

Step 3: Validating you can solve the “Collective Action Problem” by adding legitimate friction

Why is it so hard to create a solution to a problem everyone agrees with?

It’s because of collective action problems.

When the effort within a group to create a public good is concentrated amongst the few and the rewards are diffused across the many, individuals are motivated to “free ride” on the contributions of online communities.

To overcome this, you can start by only enabling active participants to enjoy the benefits of a “public good” created by the community.

You can also create a social norm in which members are expected to contribute, or forge an identity in which members feel “people like me contribute.”

So to get its first community circle of committed power users before incorporating, Subvert sought to validate that it could find 1,000 founding artist co-owners to show there is interest and find help in shaping Subvert into what users would like to have.

And they did this by creating two tiers that ensure their first supporters are motivated enough:

The paid tier ensures only non-musicians committed enough would join.

The second tier is free for musicians and labels to become co-owners, but it’s still there as a first hurdle for people to fill out an application to show they are aligned with the mission and community guidelines. Then, they get approved.

This approval process is also a way to grant founding members exclusive status they can be proud of and prompt high-quality contributions.

Subvert’s pre-launch “Join Us FAQ” also framed the contributions that could be expected by outlining the ways a member could influence the platform’s decision making by:

Voting in elections for board representatives

Participating in quarterly town halls

Voting on major platform decisions

Submitting proposals for consideration

Joining or forming working groups on specific issues

This sets the picture of what people are expected to do, even if they are not forced to do it, but shows initial co-founders are expected to contribute in some way.

They did a good job in convincing people to sign up, but of course, there were still sceptics:

So Subvert’s next step was about showing that this new model is possible.

Step 4: Building Trust

Build enough marketing

To prepare their launch and show that co-ownership was possible, Subvert planned months of content, like an email drip, blog posts with regular updates, and documentation sharing how they put their plan into action.

Their plan was to share:

If you want to see the whole email sequence, you can find it in this GDrive.

This might seem pretty trivial and basic, but I highlight it here because I see too many people forgetting to do this.

I have done this mistake more times than I want to admit, but when trying to create systemic change, we often get straight to presenting the problem and hoping this alone will be enough to convince those around us to jump on board. And I say that because I’ve often been an advocate of launching a business with the least amount of upfront costs, but launching a community projects has nothing to do with a simple freelance business or startup.

In our era of leanness and agility, Subvert’s launch is a proper example of how, when you’re aiming to create cultural change, there is still a minimum viable level of preparation you need to prepare to launch.

To summarise, for the pre-launch, Austin Robey and Subvert’s team created:

A pre-launch website featuring the essay “A Collectively Owned Bandcamp Successor” and a countdown

A Cooperative Entity and an Initial board of directors

An email campaign with 5 emails that were also recycled as blog and social media posts on Twitter, Bluesky, Instagram and LinkedIn on Austin Robey and Subvert’s pages.

The project’s documentation includes a proper About, how shared ownership, governance and funding work, and transparent sharing of funding and costs.

A 134-page physical and digital zine to explain in detail Subvert’s project and raise some funding to bootstrap the project and show people are invested enough to invest in the project.

Probably many more things hidden behind the scenes.

So my takeaway from this isn’t that we need to create this exact content each time we launch a cooperative idea, but that it’s crucial to create enough marketing and storytelling before releasing anything that aims to create compelling cultural change.

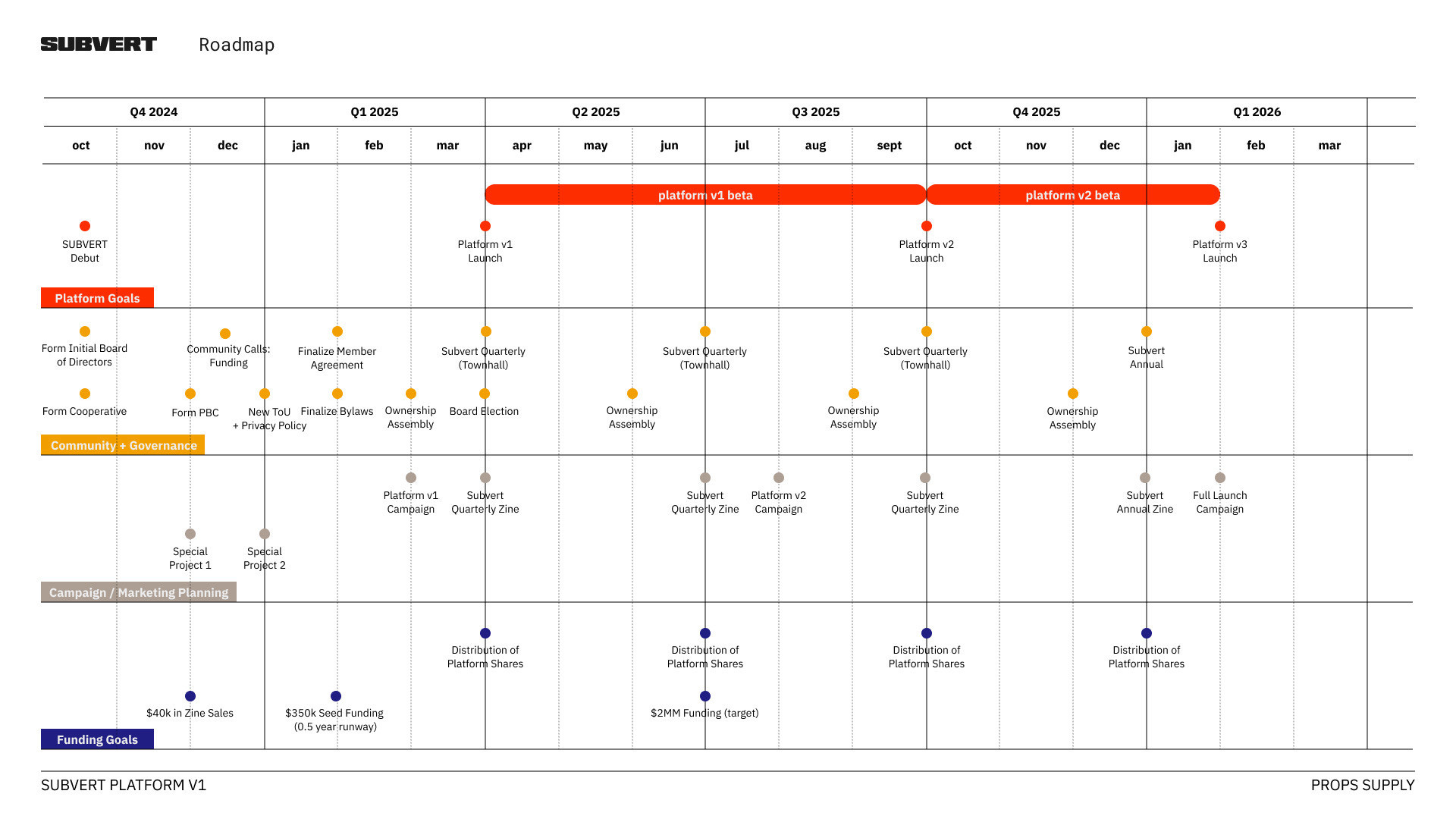

Share the roadmap

Once Subvert promises they’re going to create a collectively owned infrastructure, it becomes important for the collective to understand how they’re going to go about it and decide if they trust them to do what they say.

That’s why I wanted to insist on how important it is to share the roadmap and plans for the coming years.

First, they share a realistic plan with “small” steps.

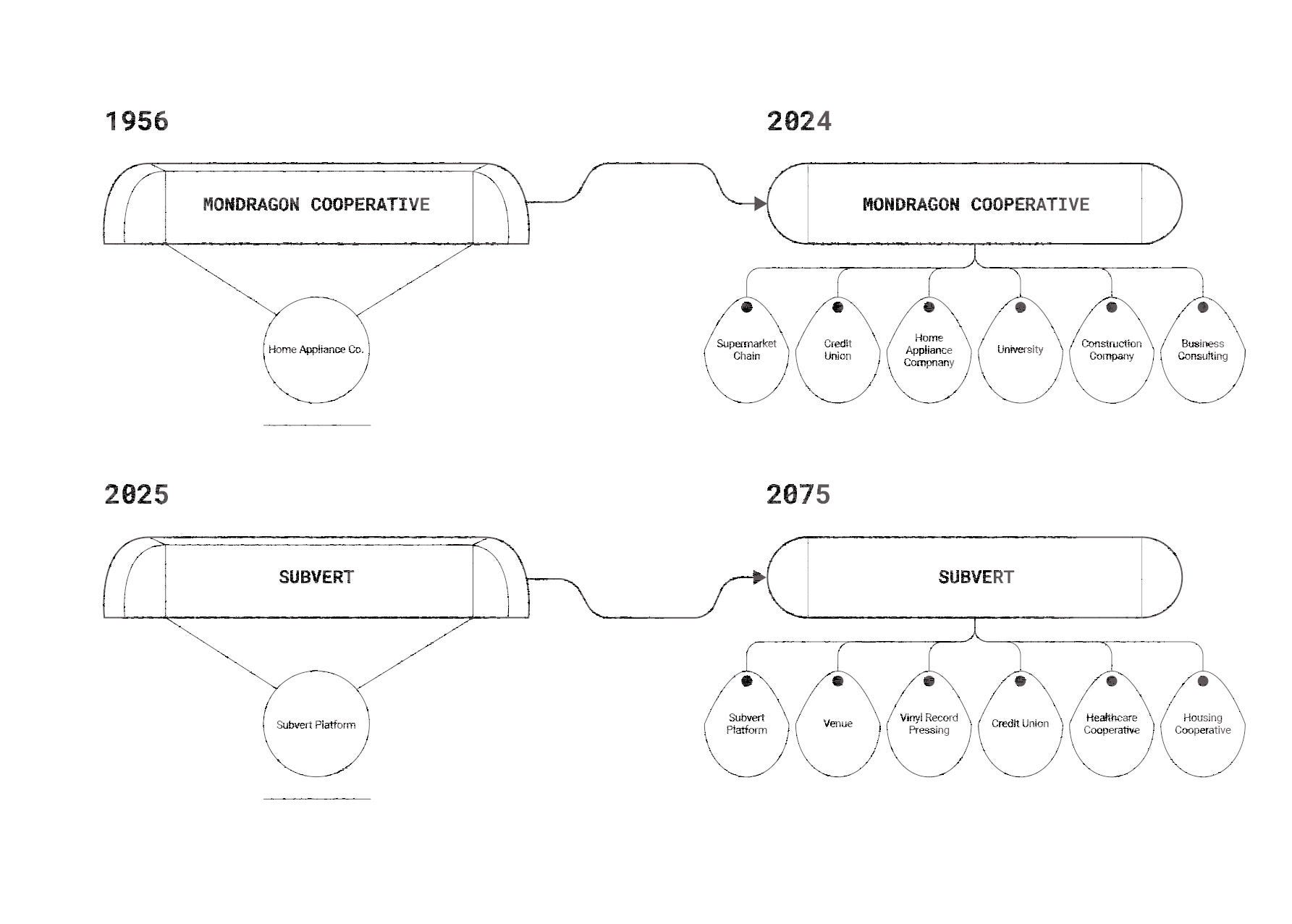

But to make this more compelling, it’s interesting to see that they have considered what might go down in 50 years and use a proven example to share how this might turn out. Mondragon started as a small cooperative manufacturing home appliances. But grew to employ over 80,000 people across different industries like banking, grocery stores, construction or a university.

So what’s possible if these learnings are applied to a music platform owned by its users? Down the line, Subvert co-op members could collectively own vinyl pressing plants, networks of cooperatively owned music venues, a credit union, professional services or a housing cooperative.

This serves to convince the early adopter that this is not just about building a music platform, but about the grander goal of creating a new economy owned and controlled by us.

But what I find most brilliant is how they transparently share the completion of their progress on their roadmap and changelog.

By showing that they’re making progress, they’re also showing that they are keeping their promises. And this is very exciting to see and makes it easier to trust the team.

Get trust through testimonials

Let’s recap. So far we’ve seen that Subvert has worked to build trust in the project and it’s vision by:

Showing the credibility of the founder and team in their “Who we are” blog article and email

Sharing their analysis of the problem: Our crisis of imagination

You might already be doing this masterfully, but the last ingredient I wanted to share is about gathering relevant testimonials to sprinkle in your website and email campaign.

I don’t know if Subvert did it like this, but I’ve found that a great way to get testimonials is to use the FIT framework:

Ask for Feedback.

Iterate on the feedback you receive.

Ask for Testimonials.

Hypothetically, once Subvert launched their first manifesto and had a first group of people signed up, they could have started reaching out and following these three steps.

If you’re launching a coop, you could ask members to give you feedback about what they wish from the platform or what problems they’d like to solve. Then you could use that feedback to drive your content, roadmap and website, and it’s also a great transition to ask for a testimonial if people like what you’re doing.

When new users see testimonials from people similar to them, it becomes easier for them to trust you.

Step 5: Bootstrapping by launching a zine

When I first read this tweet, I didn’t understand.

Isn’t a zine a badly printed magazine by underground punks? Why would people pay $100 for that?

But, as Austin Robey could have pointed out, I was pretty lacking in imagination.

He knew what he was talking about since he had already created five zines, and seen many more created as a co-founder at Metalabel.

People wouldn’t pay for the zine itself since there is a free file everyone can download. But as it released, I understood this wasn’t about getting an indie business book but about the desire to join and contribute to this movement and become the co-owner of a piece of history.

And to be honest, the zine’s design is pretty cool, and for someone who’s been craving to see platforms owned by their users for years, this is something I could get behind.

But this looks like a tonne of work. How did they fund the development of Subvert’s Zine and everything so far?

I guess there have been some initial savings, as Subvert is currently self-funded and hasn’t accepted outside investment. But the Zine’s creation was supported by two fellowship grants totalling $35K awarded to Austin Robey.

And at launch, 252 people paid $100 as supporters to get the zine, become co-owners and gain access to the community, and 1094 musicians and labels got the zine and co-ownership rights for free.

This added to Subvert’s funds around $25K.

So in total, the project has raised around $60K between their grants and the zine’s sales.

Step 6: Get the collective going

Once the ground has been set, the next step is moving from the initial team to involve the first members to help lay the foundation for the platform’s future.

Every new member has had access to:

the manifesto and blueprint through the zine.

Subvert’s members-only forum, where they’re actively shaping Subvert's development.

A chance to influence the interface and the platform's features and policies through direct feedback on designs, prototypes, and features.

This isn't just about gathering opinions. It's about building with a community and being responsive to the needs of Subvert’s members from the beginning.

Step 7: Test your hypotheses and keep improving

It’s still too early to know if Subvert will succeed or not, but I find their approach radically inspiring.

By trying once again and sharing the learnings from this attempt, we’ll be closer to having cooperative platforms.

We should all acknowledge that the life of a business is transient. Some survive and others don’t, whether they’re corporations or cooperatives. In fact, cooperatives have a higher chance of surviving than traditional companies, especially after the startup phase, and greater resilience in downturns due to risk adversity and shared sacrifice.

But if the next experiment fails, don’t declare defeat.

It’s time to learn from what failed, form new hypotheses of how it could work, and keep experimenting until we get it right.

How can you replicate some of Subvert’s successes?

Subvert’s approach has helped them gather over 1600 supporters during their launch with a vision to create a cooperative platform shared in open source and governed by the community.

Here are the key takeaways you can borrow, modify and adapt for your organisation based on Subvert’s real-life strategy and tactics:

Understand what made those before you fail, and find ways around it.

Platform coops’ Achilles heel has mainly been lack of funding and lack of a strong product-market fit. To overcome these challenges, Subvert is bootstrapping their approach by selling their vision through a zine and crowdfunding; they’re developing their product with their early community and building tonnes of trust and proof they are building with the community.Sharing ownership IS innovation, and it can give you a competitive advantage that current platforms won’t be able to match.

Build a compelling vision of why a collectively owned platform can work.

What’s your promise? How can the world be different for the people who join?

What are their objections, and how can you respond to that?What’s the plan to turn that idea into a reality?

Avoid free riders who just want to use the final solution without contributing by creating some friction, like filling out a form to show their interest to make sure you only allow in those engaged and committed enough.

Build enough marketing materials to make it obvious why people should trust you.

Explain your credentials and the work you’ve done before.

Articulate the problem you see needs to be tackled and why your solution makes sense.

Share your roadmap and ultimate vision, and display how you’re fulfilling it as you go.

Ask for relevant testimonials from your early members and followers.Find ways to fund your launch.

Subvert sells its business plan packaged as a beautiful zine, because its founder has experience producing this kind of product. But consider what other things you could sell that would be valuable to your early community to get some money flowing that’s also a natural extension of the platform you’re building and is aligned with your skills.Get your early community to collaborate and give feedback on your initial designs in a closed space to begin with. Open later.

This makes it easier for you to engage and be responsive enough to take care of the early members, create connections between them, and get them to see the impact of their feedback.And if all of this fails, don’t be discouraged.

Look at what didn’t work and take those learnings to consider how you can try again better and share it with the community so we all learn together.

Further Reading:

The Platform Coop website has an amazing library with 2000 articles and excellent courses

How to start a cooperative, by Austin Robey

Solving the capital conundrum, by Nesta

Equity-Free Fundraising: Here are our Revenue-Share Term Sheets, by Austin Robey

Antiusurpation and the road to disenshittification, by Cory Doctorow

Acknowledgements:

Big thanks to Austin Robey and Trebor Scholz for their feedback on the early draft of this article.