The Cycles of Bundling and Unbundling to Unleash the Public Sector's Creativity

👋 Hey, it’s Jaime. Welcome to my weekly newsletter where I share how thriving open source projects grow their communities.

If you’re not a subscriber yet, here’s what you have missed from past newsletters:

Why inviting others to steal your ideas can propel you forward

How FreeCodeCamp created one of the largest online community media

Subscribe to get access to these posts, and all future posts.

In this week’s newsletter, we’ll cover how some public agencies are embracing openness to create alternatives to tech monopolies, and how it can improve our agency to improve our local lives and our public services.

Read time: 8 minutes

There is a very strong myth that has taken root in our economies:

The public sector is inefficient, ineffective, and un-innovative. Where possible, it should get out of the way and let the private sector do the work, reaping the financial rewards while the risks of failure remain with the government and citizens.

But if we allow the private sector to develop with no limits, we create a world overly dependent on corporations like Apple, Facebook, Google, Amazon, or Microsoft who get to impose their decisions on us and block new regulations for the rights to repair, or measures that destroy our privacy to protect ads, profits and monopolies.

Or we get a world in which public spending funds vaccines, but patents make us pay twice and cut access to vital vaccines outside of western countries.

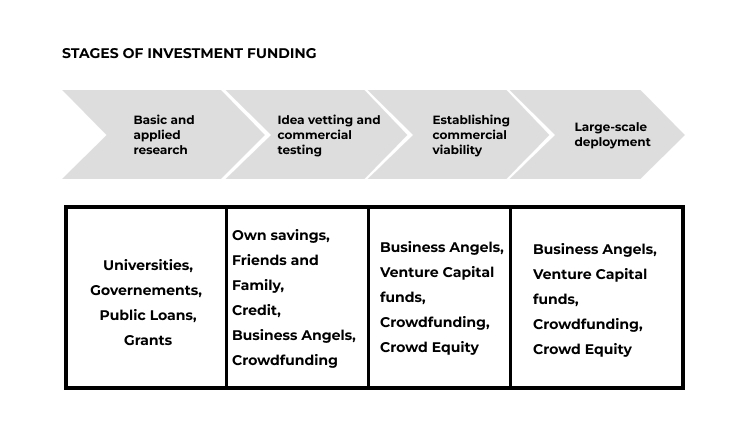

And the public sector can certainly be made better, but without it, no major innovation could take place, as the government is the only actor able to invest in very high-risk innovations. As Mariana Mazzucato has shown in the book The Entrepreneurial State, public investment is the only actor able to invest in very risky technologies like sending a human to the moon, the internet, smartphones, medicines, renewable energy, and other university research. These breakthroughs are first funded by the government, and once they show proven results and are not risky investments anymore, they can be taken and deployed more widely by the private sector.

But since the last 10 years, in the name of modernisation, rationalisation, and efficiency, countries like the United Kingdom or France have shrunk their spending towards public capacity building and increased their spending to outsource core elements of public initiatives, like the track and trace COVID program, to private sector consultants.

And here is the pattern that weakens us all:

The more our public sector relies on external consultancies or centralised systems like the GAFAM, the more we weaken our capacity over time and lose our capacity to do things ourselves, creating dependency, taking away our agency as citizens, and infantilising our public departments.

Instead of wasting billions on external consultancies and proprietary technologies that stand to benefit from the hollowing out of the public sector, open source technologies and the natural world, governments should invest internally in creating capable organisations that foster learning and are empowered to take risks.

But what could this look like?

An opportunity for the public sector to break our dependence on monopolies

In 2010, Andrew Parker, a VC investor, wrote a post about the "unbundling" of Craigslist, where he outlined the opportunity to carve out niche products from broad horizontal networks like Craigslist.

Another example is the way Google’s Suite is being unbundled by other services:

Smaller startups or open standards and platforms rise to poke holes into these monopolies.

The destiny of every massive social network or marketplace is unbundling. It's ,not a matter of if but when.

This happened in the 1980s when the hardware and networking monopolies of AT&T and IBM were contested by other computer providers and the rise of modem. In the 1990s, Microsoft and AOL had a monopoly on the internet and software, but then came Linux and open protocols. In the 2000s, the openness of Android challenged the closed monopoly of Apple.

And there are many examples where open source has taken over proprietary solutions:

Encyclopaedia Britannica —> Wikipedia

Blogger —> Wordpress / Ghost

Proprietary 3D Printers —> RepRap and 3D Prusa

Adobe Maya —> Blender

Windows & MacOS —> Linux / Ubuntu

Github —> Gitlab

Google Maps —> Open Street Maps

Shutterstock —> Unsplash

Intel Processor Architecture —> RISC-V

Calendly —> Cal.com

OpenAI —> Hugging Face / Meta’s LLaMa

and thousands more…

Today, the public sector can play a new role in balancing the scales to further break down monopolies, multiply its capacity to tackle large challenges, create collective wealth and improve its citizens ability to participate in the economy.

The public sector can produce new open source alternatives by unbundling the existing monopolies, or it can financially or operationally support those that create open alternatives. Here are some French examples I’m well acquainted with:

The SNCF, the National French Railway, has broken its dependency on proprietary suppliers by creating open source tools that it now mutualises with other European railway organisations through the Open Rail Association.

The ADEME, the French agency funding the ecological transition, has created new funding tools like the Call for Commons to support open source solutions that contribute to improving our ecological resilience.

The IGN, the French Geographic Institute, is creating Panoramax, an open alternative to Google Street View.

The French Ministry of Education adopted and financially supported the development of Big Blue Button, an open source alternative to Zoom.

And when looking to build a test and trace system during COVID, instead of spending hundreds of millions of pounds like the British government on malfunctioning proprietary solutions from private consultants, the French Social Security Agency (CPAM) partnered with the very nimble NGO Bayes Impact. The CPAM integrated Bayes robust open system, which notified 10 million+ individuals and became France’s official contact management system.

But public funding is also responsible for supporting other open alternatives outside of France:

In the US, the DARPA and the State of California funds have supported the RISC-V’s protocol research to open the field of processors away from the oligopoly of Intel, ARM, or IBM and create new opportunities for an entire market.

In Slovakia, the city of Bratislava has launched Bratislava ID, which can be reused by other municipalities worldwide to make access to digital services easier, faster, trustworthy, and more transparent. It offers the option to pay property tax fully digitally, buy a ticket for an outdoor swimming pool through a single sign-in, and collect all the links for city services provided through other websites. Like France Connect, these open ID services create a powerful alternative to Google’s or Facebook’s sign-up systems.

But isn’t this unfair competition with the public sector?

To some, this might sound like the public sector is using its access to public funds to distort the market. But it’s only taking away the capacity of monopolies to lock a market from competition and maximise their profits.

Favouring the emergence of open source helps to encourage the creation of an environment conducive to competition and innovation. This also has beneficial consequences for everyone, like lowering prices as well as improving well-being and economic opportunities.

This strong link between open source software and undistorted competition has been confirmed by various court rulings in recent decades (see Italian Constitutional Council, 23 March 2010, 122/2010).

In 2018, the European Commission released a surprising report on the impact of open source software and hardware on the European Union’s economy. The study found that European Union companies invested 1 billion euros in open source software, and this investment was estimated to contribute between 60 and 95 billion euros to the EU’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

If it sounds like investing in software is like creating free money, it is because it actually enables extra capacity in the economy that wouldn’t be possible otherwise.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica’s salesmen hated Wikipedia. But when we went from the Encyclopaedia Britannica to Wikipedia, it enabled everyone to go from accessing a few hundred editors and forty thousand articles to tens of thousands of editors and over fifty-five million articles in 309 languages.

Instead of wasting billions on external consultancies and proprietary solutions that benefit from artificially creating collective scarcity, governments should invest internally in creating capable organisations that foster learning and are empowered to take risks and open tools that empower their citizens to participate and learn, which also multiplies the capacity of the administration.

The more we rely on centralised monopolies and the consulting industry to deliver critical policy and service functions, the less our democratic system is able to maintain our capacity to confront the challenges of the future, from climate breakdown to sovereign autonomy to health emergencies.

It is time to put an end to today’s “regime of government by private corporations” and instead invest inside our public sector, building an economy that serves the common good.

Takeaways and action items

It’s incredibly easy to believe the narrative that only Silicon Valley and venture capitalists are responsible for innovation. But there is a crucial public investment step before any of that is possible, and if we manage to share this public investment research in open source, we have the potential to multiply what it can do by empowering everyone to participate and make it better.

Takeaways:

Investing in external consultancies or centralised and proprietary systems weakens not only our public agents' capacity to act and improve their tools but also our capacity as citizens to influence the tools that affect us.

Instead of becoming dependent on proprietary services and paying whatever prices they ask for once a public agency is locked in, investing in open source technologies reinforces the capacity of the public sector to have control over their tools and enables other ecosystems of actors to collaborate and amplify what the tech is able to do.

Whenever there is a monopoly, it would make sense to invest in the creation of new open standards that can be shared across industries or by supporting smaller startups or collectives developing open alternatives that can challenge that excessive power.

I’d love to get your help growing these examples of open leaders and creators in the public sector. If you, or a friend, know other examples and inspiring stories, would love to read you in the comments. Or if you prefer, feel free to send me a private message.

Be great,

Jaime

Sources:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/sep/20/britain-public-sector-consultancy-habit-pandemic-private-services

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/feb/28/uk-ministers-consultants-whitehall

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affaire_McKinsey