What should become open source and what should stay proprietary?

👋 Hey, it’s Jaime. Welcome to my weekly newsletter where I share how thriving open source projects grow their communities.

Subscribe to get access to these and all future posts.

Today I’ll cover a question that I’ve been looking to answer clearly for a while. What should be legitimately opened or closed?

As a business, it’s hard to contemplate opening something when most forces push us to patent or protect our ideas to raise funding and whatnot.

But are businesses and society missing on bigger opportunities when we close something?

We’ll cover:

What world do we want to create?

Understanding what is scarce, and what’s abundant

Who pays the bill for creating open and abundant things that cost a lot of money and time to develop?

So what should be open or closed, and how?

How to put this in practice

If you’re in business to maximise your profits, this article is probably not for you. But if you’re in it to create something meaningful and impactful, while you, your colleagues and the planet are able to live comfortably, I suspect you’ll find it interesting.

This is still a reflection in progress and probably one of my most experimental articles as it includes more political and social considerations, so I would love to hear your feedback on this article, and what might be some blind spots I’m missing.

Read time: 18-ish minutes

A few months ago a friend invited me to do a conference in front of a group of award-winning startups, and he asked me to “please be pragmatic about what could be open sourced by business people.”

But even if I called my organisation Bold & Open, which might suggest I would push everyone to go open no matter what, I was happy to take on the challenge.

What a question! Is there a legitimate limit to what should be opened or kept closed?

Before answering that, let’s zoom out a bit on the social implications of the way we develop our startups and businesses today:

A few months ago a friend invited me to do a conference in front of a group of award-winning startups. He asked me to “please be pragmatic about what could be open sourced by business people.”

But even if I called my organisation Bold & Open, which might suggest I would push everyone to go open no matter what, I was happy to take on the challenge.

What a question! Is there a defined limit to what businesses should or should not open up?

Before answering that, let’s zoom out a bit on the social implications of the way we develop our startups and businesses today:

What world do we want to create with our work?

When we create a startup, a business or even choose to work for someone else, our work has short- and long-term effects on the rest of the world.

As I see it, today, there are two main ways of creating a business:

The mainstream way of creating businesses is about productive assets (machines, software, factories, supermarkets, companies, etc.) owned and funded by a few, hoping to build a market position that is strong enough to be able to control prices so they can make the most profit for the owners and investors.

This is the equivalent of creating things like Twitter, Intel, a supermarket or a fast-fashion brand.The “Commons” or “Open source” way of creating the same productive assets, but instead of letting them be owned and funded by a few, they are owned by everyone and no one at the same time. This can be by open sourcing the intellectual property, like public research or open source projects like Bluesky and RISC-V, or by governing these assets in common and distributing their profits to owners, investors and employees, like cooperatives or consortiums do.

Today, our system favours projects run in the mainstream way. Once the business becomes mainly accountable to investors, it is probably the most lucrative path for both investors and founders if they’re able to turn their company into a monopoly or oligopoly. Even if the founders have the best intentions, once they have to constantly appease investors with ever-increasing profit cycles, they won’t be able to stop the natural tendency towards the enshittification of their business. Otherwise, investors will pull out their money, and it’s game over.

Enshittification is a word coined by Cory Doctorow. It means that, initially, vendors create high-quality offerings to attract users, then they degrade those offerings to better serve business customers, and finally degrade their services to users and business customers to maximise profits for shareholders.

A few examples of these are platforms like Airbnb, Amazon, Facebook, Google Search, and Twitter, but also most main retailers, clothing brands and so on…

But we’re also seeing through the WP Engine drama how someone like Matt Mullenweg is taking decisions that affect the entire WordPress ecosystem without its members’ consent.

So, in the long term, a lucky few end up being rewarded with extreme wealth and power, while the rest of society is penalised with worse and more expensive services and little power to change it.

The “Commons” way favours projects maximising collective interests. That means creating open and community-driven initiatives. This way has more constraints, as it’s harder to find investors or customers. As such, it probably won’t make you a billionaire, but you can still build a viable business and live comfortably. And since this approach prioritises creating systemic change and collective well-being, it has a higher potential of attracting collaborators and decreasing the need for resources through mutualisation, making the commons approach much more resilient.

So yes, there are trade-offs, and only you know how you want to run your project.

With that said, let’s go back to our initial question: Is there a defined limit to what businesses should or should not open up?

I believe there is. In my experience, the boundary depends on whether something is abundant or scarce. And this has many business implications that I’ll try to examine.

Understanding what’s scarce and what’s abundant

Let’s first use a quote you might know to define scarcity and abundance:

“If you have an apple and I have an apple and we exchange these apples then you and I will still each have one apple. But if you have an idea and I have an idea and we exchange these ideas, then each of us will have two ideas.” - George Bernard Shaw

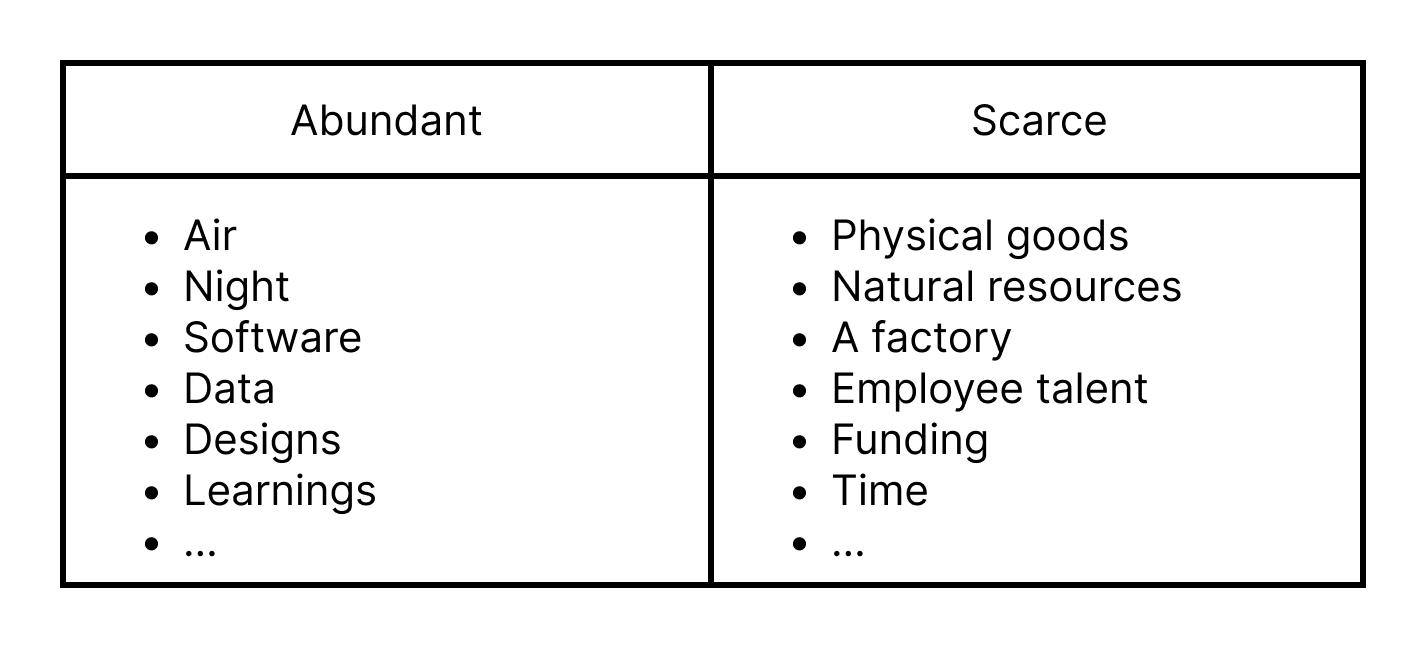

So something scarce (or rival) would be something that decreases or disappears once you share it. These are often physical or finite things:

Physical goods like a car or clothing

Natural resources like a forest or food

A factory

Employee talent, skills and time

Funding

Time

There are also things that are scarce because they’re impossible to share:

Your relationship with an audience, your community, providers, or distributors

People’s or customers’ trust in you or your Brand

Your Leadership

Your intimate understanding of your audience’s needs

And something is abundant (or non-rival) when it remains the same or multiplies as you share it. These can be things like:

Air

Night

A beautiful sight

Software

Data

Designs

Learnings

The mission you’re on

And there are things that I can’t quite decide whether they are scarce or abundant, like taking a decision or making a choice for your organisation (aka governance).

Bottom-up decisions can be shared collectively through consensus, or top-down decisions can be kept to a single person who decides for everyone.

But we’ll come back to this idea of governance later.

To illustrate these ideas of scarcity or abundance more concretely, you might remember the famous anti-piracy campaign that claimed that You wouldn’t steal a car to denounce online piracy.

Except cars and mp3 files are nothing alike. One is naturally scarce, and the other is naturally abundant. If you give a car away, you don’t have it anymore. But if you let other people copy your mp3, you’d still have it.

When sharing data or software, they can be endlessly replicated. If a developer or a data center consumes code or a data point, this doesn’t mean an extra person using it will delete the initial source. In fact, the opposite happens. The reuse of data usually creates more data known as metadata. And reusing code often creates new use cases.

If you share the mission you’re on, like cleaning beaches from garbage, this not only won’t stop you from cleaning on your own, but it might get other people to join you, as happens with the Let’s Do It movement that started in Estonia and spread worldwide.

Thus the value of shared data, code, research and many other things is multiplied in the flows and exchanges rather than in their accumulation.

If we’re not sharing, or if we’re putting barriers around something that’s naturally abundant, we’re creating artificial scarcity.

This can be very lucrative, as it can lead to monopoly power, as we see with the GAFAM, or with Open Core projects, where you open source some feature-limited version of a software product while offering “commercial” versions or add-ons as proprietary software.

But it inevitably leads to problems. The GAFAM have become monopolies we’re stuck with, instead of the internet we want.

And to develop their businesses, some open source projects have limited their features to Open Core models, which has had the unintended effect of driving away their collaborators and creating more open competition through people forking their projects to overcome their limitations.

Elastic is a prime example of where this happened. After building a successful OSS search engine, Elastic watched as multiple companies—AWS among them—built services directly on top of it, competing with Elastic’s own offerings.

This resulted in Elastic shifting the licensing for Elasticsearch in a desperate attempt to limit the exploitation of their code by competitors, resulting in a storm of criticism and confusion in the community. And a successful fork from Amazon Web Services (AWS) to create OpenSearch, which has gained significant traction in the open source community.

But seeing the negative effects, Elastic backtracked:

After a three-year detour into source-available licensing to mitigate competition from unlicensed commercial providers, Elastic recently reintroduced Elasticsearch and Kibana under the AGPL, an OSI-approved license. This choice reestablishes Elastic’s commitment to the open source community and allows developers to trust that their contributions will support a fully open and transparent project.

Elastic de facto embraced an open-foundation model […], which allows it to differentiate its commercial offerings without withholding core functionalities from the community. By nurturing foundational projects that complement its enterprise products, Elastic can maintain a clear boundary between free community use and paid enterprise features — one of the key lessons many companies are learning as they move beyond open-core.

— Or Weis

My takeaway from Elastic’s backtracking is that building completely open source projects fosters lasting community support and avoids the pitfalls of models that attempt to restrict usage or lock in customers. When given the choice, users will always choose the more open version available to them.

Similar things happened when Terraform and MySQL switched to the open core model, resulting in new competition to the originals in the form of popular, community-driven open-source alternatives.

And when MakerBot started patenting ideas that their community had contributed, it destroyed the relationship with their supporters. Since then, MakerBot hasn’t been able to keep up with its open competitions and has laid off 20% of its employees in 2015 and 30% in 2017.

Now we have a first distinction between abundance and scarcity. And we see that artificially closing something abundant, even in a business setting, can lead to many problems and cut us off from the abundant collaboration of other communities.

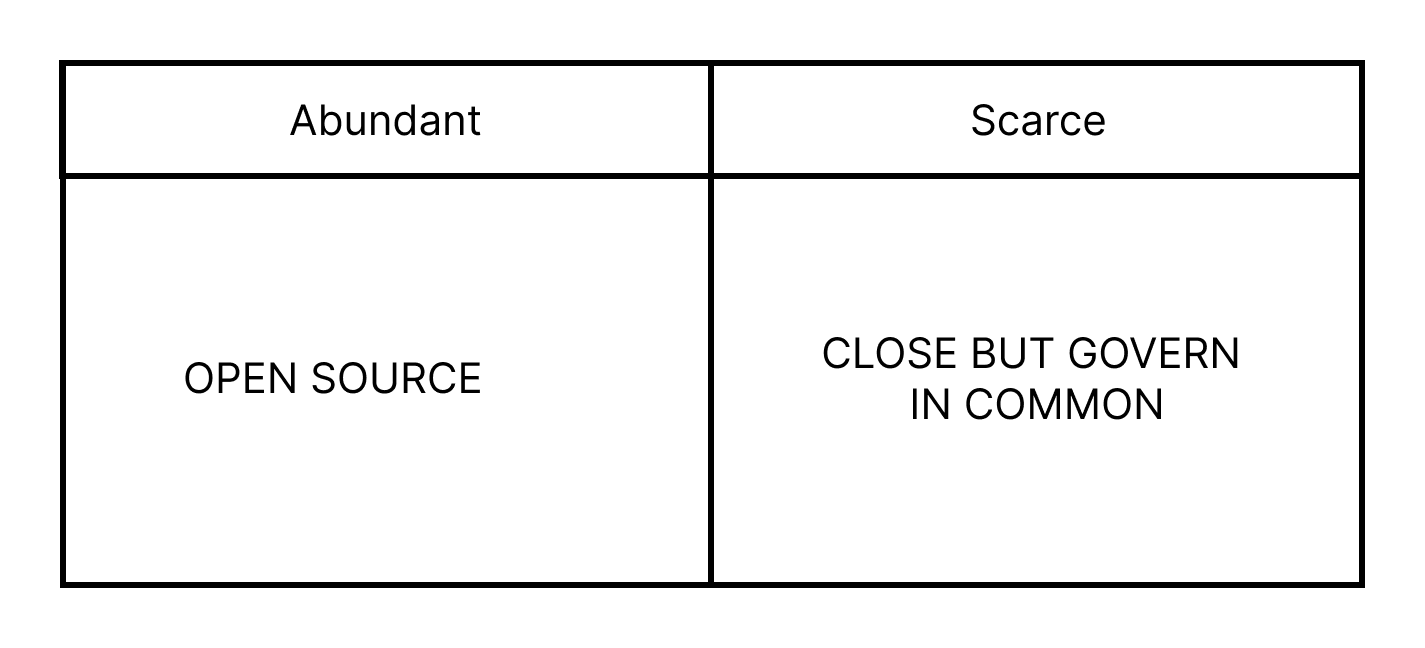

So my first rule would be that what’s abundant should ideally be open sourced, and what’s scarce should be protected.

But just leaving it at that might leave you with a lot of open-ended questions and legitimate frustrations.

So let’s not stop here:

Who pays the bill for creating open and abundant things that cost a lot of money and time to develop?

So far, the problem with my argument is how do you pay the people who create the creation of these abundant assets?

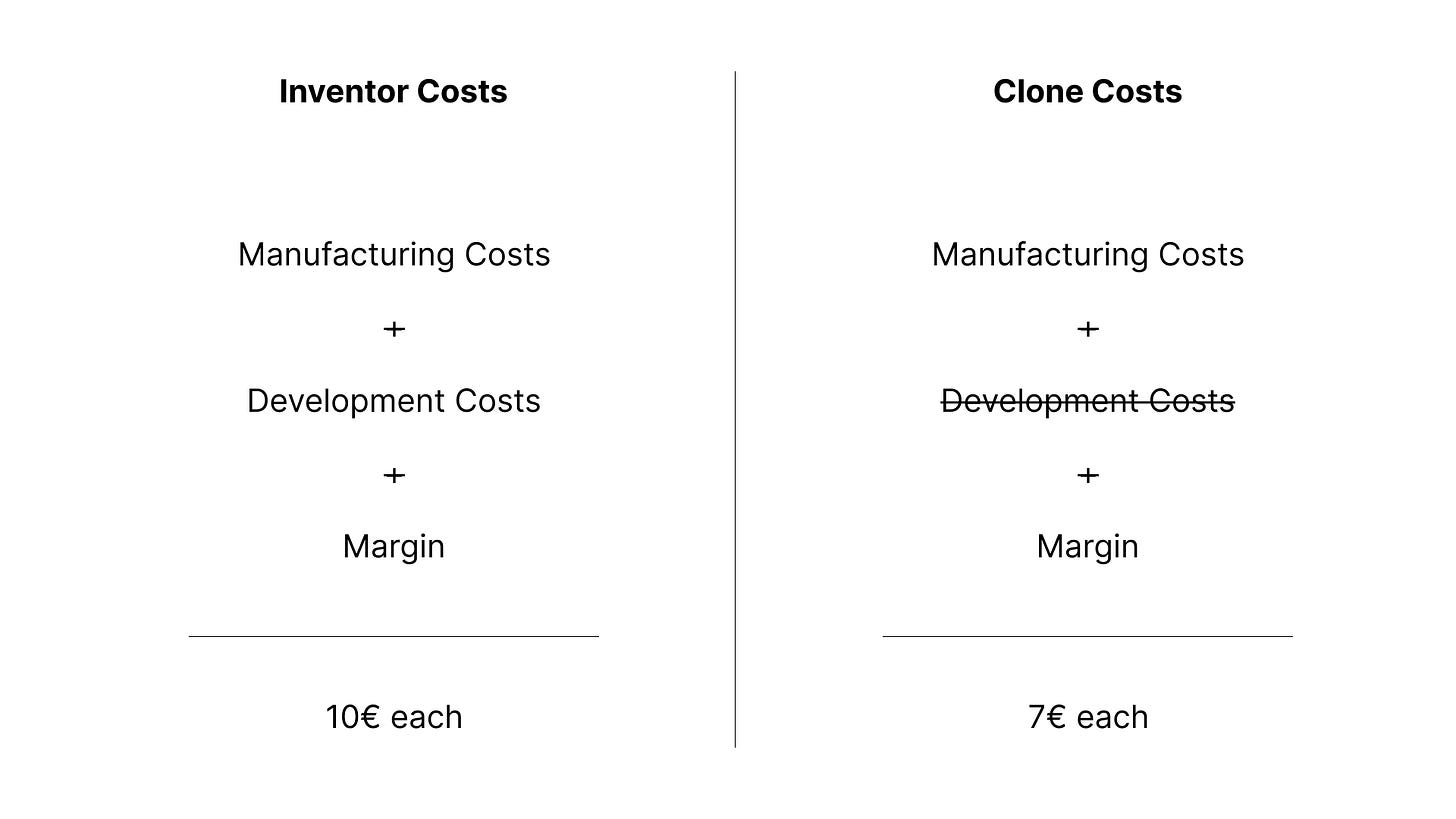

In Everything is a Remix, Kirby Ferguson explains it with a story around the cost of inventing:

“Let's say a couple of people invent a better light bulb. Their price needs to cover not just the manufacturing cost but also the cost of inventing the thing in the first place.

Now let's say a competitor starts manufacturing a competing copy. The competitor doesn't need to cover those development costs so their version can be cheaper than the original.

The bottom line: original creations can't compete with the price of copies.

In the United States and Europe, that’s where copyrights and patents came in to address this imbalance. Copyrights covered media like music and literature, and patents covered inventions. Their goal was to encourage the creation and proliferation of new ideas by providing a brief and limited period of exclusivity. A period where no one else could copy your work, so creators had a window of time to cover their investments and earn a profit.

20 years for patents and the life of the author plus an additional 70 years for copyright. After that, their work enters the public domain, where it can spread far and wide and be freely built upon.

This was the goal: a robust public domain and an affordable body of ideas, products, arts and entertainment available to all.

The core belief was in the common good; what would benefit everyone. But over time this principle transformed beyond recognition. Influential thinkers proposed that ideas are a form of property, and this conviction would eventually yield a new term: intellectual property.”

Creating artificial scarcity around something that’s abundant by allowing ideas to be owned has led to destroying our collective benefit.

But how do we address creators and inventors having to compete with those who can copy them at a lower cost?

As Nadia Asparouhova (aka Nadia Eghbal) surfaced in her brilliant report Roads and Bridges, today, most of the digital infrastructure we depend on is open source, and these open infrastructures are not maintained because their creators need to work on something else to fill their fridge and put a roof on their families heads. This is mainly because we haven’t found a way to develop reciprocity mechanisms where the ecosystem using and making money out of open source can give back to those creators they depend on.

This lack of reciprocity mechanisms between the ecosystem that depends on open source towards open source creators makes us all vulnerable. Not only is the ecosystem not giving back, but sometimes it is actively competing with the open creator, as we’ve seen with Amazon offering a competing copy of Elastic Search or the recent drama between WPEngine and WordPress.

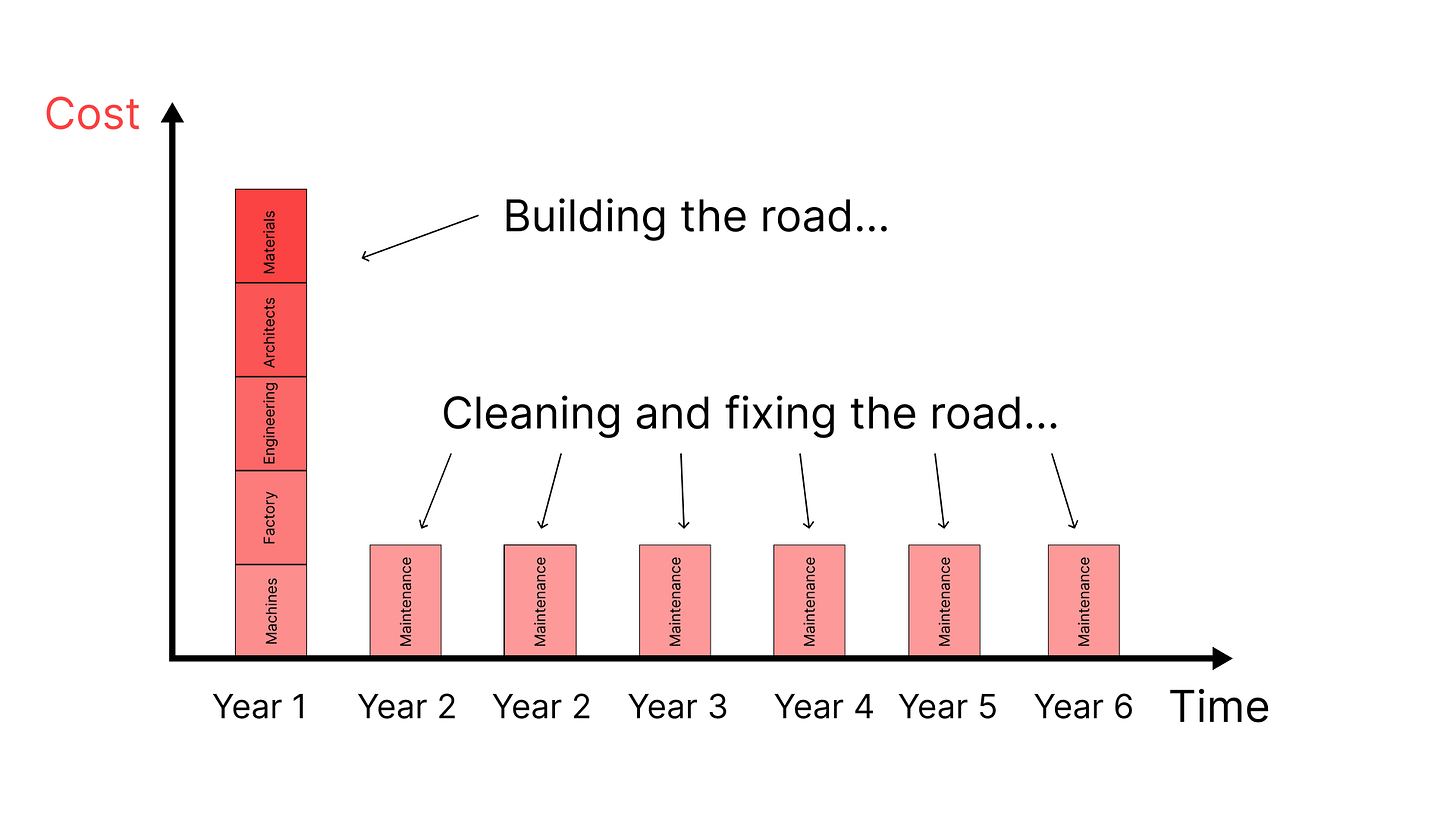

And creating those open assets is only the first problem.

Once we manage to create these assets, then comes the second problem of funding their maintenance.

Because it’s great having a new paved street, but if no one cleans it or comes to pick up the garbage, then it becomes unusable. The same happens with most open source code. Even if Linux is free, you still need people to improve and debug the code, to educate, coordinate, deal with conflicts and review contributions.

With all of these obstacles, how do we fund or find customers to create and maintain these abundant assets when everyone has access to them?

Here are some ways:

Building businesses or non-profit revenues around what’s naturally scarce.

As Joel Spolsky points out, when a new technical breakthrough makes something abundant, it increases the demand for its scarcer complements. For example, when a piece of software becomes a commodity, there is increased demand for its complements, like consulting services, servers, or support.

Even when everything can be accessed for free, as Kevin Kelly points out in his book The Inevitable, naturally scarce things will remain impossible to copy, store or clone, like immediacy, personalisation, interpretation, authenticity, accessibility, the physical version of a digital good, supporting a creator you love, or curating those billions of freely available things…

So no matter how many things become abundant, there will always be scarce things around which to build businesses.Crowdfunding or raising crowdequity with your community.

If venture capitalists or banks don’t want to fund your idea, there are other options. If you build your idea in public and manage to gather an audience or community around your project, you might find ways to pre-sell or crowdfund your products or services to fund your initial investments or to raise more to scale through crowdequity.Creating public funds that support open infrastructures on which we all depend.

Governments already know how to build abundant assets like roads or electrical grids. The next step is to fund the development of open source and common infrastructures.

These funds should cover the high upfront costs of developing them (technical, design, documentation, community development, etc.) and also cover the lower, longer-term costs of maintaining these infrastructures (bug cleaning, community development, improvements, etc.) or can dedicate teams to keep maintaining and improving the commons.

Some examples of this are the Sovereign Tech Fund from Germany, NGI Commons from the European Commission, or La Suite, the french Dinum’s initiative to create or support existing open source projects to create a sovereign alternative to Google Drive or Microsoft Office.

And there is another thing to consider: you need to raise a lot less money to pay for R&D, spaces, employees, materials, marketing, legal fees and so on.

To use economic jargon, investing in abundant assets like open source software or hardware is extremely capital efficient. In simpler words, it takes less money to develop the same stuff because you only have to make the initial investment once, and people can collaborate with others instead of having to raise funding and develop redundant and competing versions each time someone wants to create their alternative technology.

For example, in 2018, freeCodeCamp.org had a $200,000 budget, and with that, it was able to get more visits than Codecademy, a coding education startup that has raised $47 million, and Udacity, a corporation valued at $1 billion, making it probably “the most capital-efficient organisation in modern history.”

Another example is RISC-V’s open-chip architecture ecosystem that's doubling every year and was expected to go from $52 million in 2018 to $1.1 billion in 2025.

Arduino or open source 3D printing have been

Ok, we now have a distinction for things that are abundant, scarce, and ways to fund the building of these abundant assets.

So let’s go back to our initial question:

What should be open and what should be closed?

By now you probably know what I’m going to say.

I believe we should open what’s abundant. Otherwise we’d be creating artificial scarcity and preventing collaborations from happening.

“The cultural commons, particularly software, doesn’t get used up when more people contribute to it. In fact, it gets better.” - Seth Godin

And we should close scarce assets to avoid them from becoming another tragedy of the commons. But with one big condition. Scarce assets should still be governed in common by the community of actors dependent on them.

Otherwise, as we’ve seen with the enshittification of Facebook, Amazon, Twitter and so on… Executives that control these platforms can decide against the best interests of those users that contribute to making them valuable but who have also become dependent on their assets.

Instead of waiting to become the next platform to betray our communities trust, the alternative involves proposing accountability agreements between founders, community and investors.

Elinor Ostrom argued that in many settings, 8 principles can produce resilient and effective ways for managing commonly shared resources:

Clear boundaries defining who has rights to use the resource

Rules that match local needs and conditions

Systems allowing most users to participate in modifying the rules

Effective monitoring by accountable monitors

Graduated sanctions for rule violators

Low-cost and accessible conflict resolution mechanisms

Recognition of community self-determination rights by higher authorities

For larger systems, organization in multiple nested layers

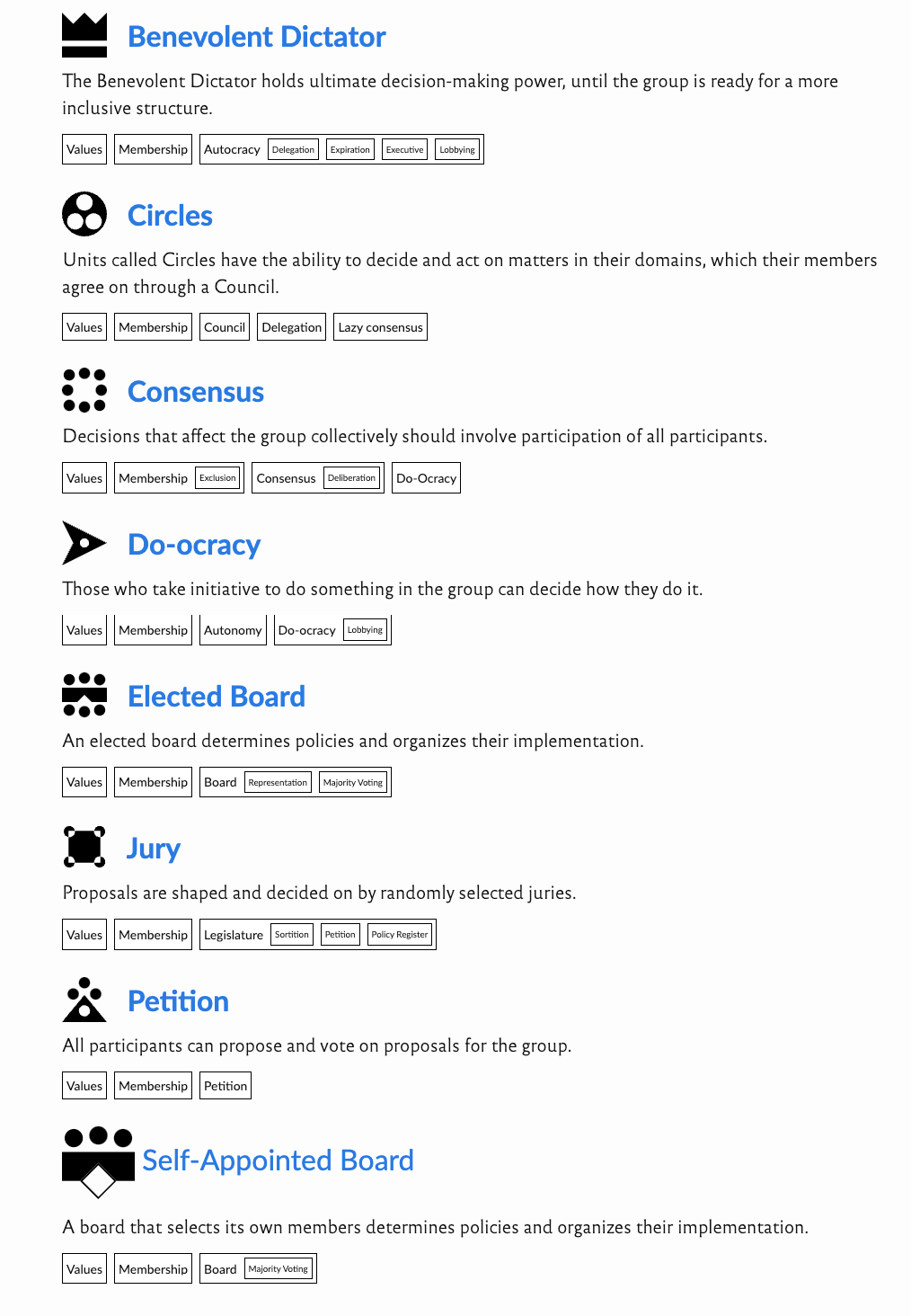

Here are some handy templates of some governance forms a community can adopt, by the Media Economies Design Lab :

If you’re a business leader reading this conclusion, you might find the idea seductive but scary at the same time, as you might wonder how you’ll find ways to develop your business or find investors for your idea.

To develop your business, you will still be able to build your competitive advantages on what’s naturally scarce, like:

brand reputation

network effects

relationships with your customers

understanding what your community needs

your factory’s performance

your distribution channels

the talent of your teams

or your delightful support

There are very large-scale organisations like Wikimedia, RISC-V, or the Open Rail Association made up of many startups and public or private companies building their infrastructures on top of shared open architectures or tools.

There are medium-scale organisations like Team for the Planet in France raising millions in funding to develop dozens of climate startups.

There are smaller-scale startups like Subvert creating an alternative to closed platforms like Bandcamp by offering their community to govern the platform in common.

This is easier to do with software, since it costs a lot less to develop, but there are many hardware products that have found ways to thrive, like Arduino, Adafruit or 3D printing companies like Prusa3D. And it’s also a financially sustainable way to develop public research, as shown by CERN.

As Miriam Gradel from HardwareX points out, this is also fertile ground for hardware non-profits, as “the open access to rapid manufacturing and open-source computation has resulted in generations of developers and inventors that are picking up where public sectors and private companies are falling short to meet urgent needs across the globe. [We can see things like] 3D-printed tourniquets for Gaza/Ukraine or community-driven environmental monitoring using RaspberryPi.”

And I’m aware that what I’m painting in this article is still an ideal future for most of us.

A few actors like the ones above are already experimenting with openness and shared governance. But I don’t blame you if you don’t feel ready to do it yet. Instead of going straight into open sourcing your product, you might consider sharing some of the tools or templates you’ve developed internally and mutualise them with your competition.

And if you don’t feel ready to govern all at once with your competition, providers, employees, customers and environmental non-profits, you might start getting only one collective at a time into your governance and developing your collaborative skills little by little.

As more people get tired of platforms controlling them by imposing artificial scarcity on them, there will be more and more entrepreneurs building their competitive advantage by creating truly abundant assets and building them with their community.

As I write this in early 2025, we see how millions of people are moving from Twitter to Bluesky or Mastodon, or closing their Facebook, Instagram or Threads accounts. Or how China’s DeepSeek blew a $1 trillion hole in the proprietary AI race.

How to put this in practice?

Ready to explore opening what’s abundant and govern together how you run those scarce assets?

And here are some questions for you to consider if you want to expand beyond your proprietary or Open Core offers:

What’s naturally abundant or scarce in your project? Consider opening them. Are there designs, code, data, methods, content or knowledge that others would be interested in using and contributing to developing or distributing?

What becomes scarce that becomes more valuable once you open source what’s abundant? What are the complements of that abundant thing you’re sharing that you can sell? This could be things like:

Services

Consulting

Servers

Support

The physical version of a digital good

Customisation

Immediacy

interpretation

Authenticity

Accessibility

Patronage from people who love you

Curation

A Consortium that members pay to pool the costs of development and maintenance

What scarce assets do you have that you can build your competitive advantage on? This can be things like:

brand reputation

network effects

relationships with your customers

understanding of what your community needs

the performance of your factory

your distribution channels

the talent of your teams

or your delightful support

If you open your governance to those who depend on your project (like your users, employees, investors and so on…), consider how these 8 principles would apply to managing your shared resources:

Access: Who has rights to use the resource so the users receive the benefits of cooperating?

Rules: Rules that match local needs and conditions

Participation: What systems would allow most users to participate in modifying the rules to their local context and ensure a certain level of buy-in to the resulting institutional arrangements?

Monitoring: Who would be accountable in the community to monitor the commons effectively to adapt the institutional arrangements if the commons conditions change, or that some users don't cheat excessively and overuse the commons?

Sanctions: What graduated self-sanctions would be needed to deter rule-breaking without diminishing social capital with excessive punishment?

Conflict resolution: What low-cost and accessible conflict resolution mechanisms are there so that a community can move forward in a way that is considered fair and acceptable by those involved?

Recognition of local self-determination: In nested systems, it is important that governing bodies allow local resource users to design their own institutions. This helps ensure that there is local buy-in to these institutions and that they are suited for the local environment.

Nested Layers: If you have a large system, how can you organise it in multiple nested layers with smaller local units?

If we let go of the temptation of creating artificial scarcity and learn how to open source everything that’s abundant and close what’s scarce while governing it in common, we might build businesses that support a society where we can collectively participate, have a voice and belong to.

Big thanks to those who inspired this article through our conversations and their work:

Javier Creus from Ideas for Change

Manel Heredero from GreaterThan

Virgile Deville from the french Dinum and Open Source Politics

Miriam Gradel, Media Editor at HardwareX

Gaël Giraud’s course on Sator

Or Weis, CEO and co-founder of Permit.io